We've known git for a very long time, it's a tool used by almost every software developer. It's not because we are used to our branching system, that it's still the best method for an ever evolving software development world. This article will be a bit more theoretical but I'll try to highlight the issues with practical examples. Currently, these are the most popular git branching strategies:

- Branch for each environment

- Gitflow (develop and main branch)

- Trunk based development:

- Commit directly to main

- With feature branches and PR's

- Release flow

- GitHub Flow

We are not going into detail of each strategy, but we can make a distinction using 1 important concept: the amount of long lived branches. Environment branching and gitflow have multiple long lived branches. Trunk based development only has 1 long lived branch.

I want to assess the differences from 2 POV's: from the software- and devops engineer. So, I'll try to answer the following questions:

- How are hotfixes handled?

- How do we decide which code is on which environment?

- How do we handle environment promotion?

- How much git maintenance is needed?

- For which projects are these recommended?

Multiple long-lived branches: Gitflow, environment branching

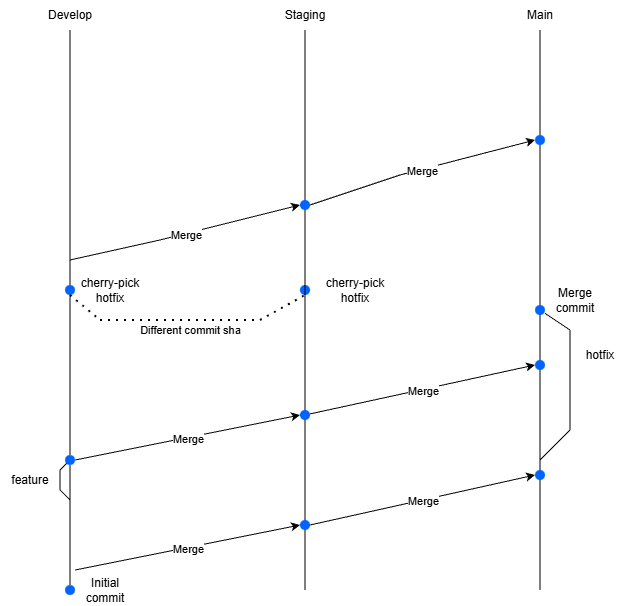

For this section, I'll use "Environment branching" since it will highlight the problems even more with having multiple long lived branches. In this example we will have 3 branches: develop, staging and main. They all reflect to their own environment.

Hands on

Let's create a local git repo, create an initial commit and create those branches:

mkdir mygitrepocd mygitrepogit config --global user.email "[email protected]"git config --global user.name "visitor"git initgit checkout -b developecho "Hello world" >> readme.mdgit add .git commit -m "Initial commit"git checkout -b staginggit checkout -b main

We will do a hotfix, we create a hotfix branch and apply a change there:

git checkout -b hotfix/branch-1echo "Hello world!" >> readme.mdgit add .git commit -m "Updated readme.md"

Now we are going to simulate that someone is working on a feature meanwhile and commits to develop (in practice they would use feature branches and create a PR).

git checkout developecho "Hi from develop!" >> develop.txtgit add .git commit -m "Added new feature"

That developer tested his changes on the develop environment and is happy, he merges to staging. Staging is also looking good and merges to the main branch.

git checkout staginggit merge develop --no-editgit checkout maingit merge staging --no-edit

Let's merge our hotfix and watch our commit history.

git merge hotfix/branch-1 --no-editgit log --oneline

Now the maintenance begins, the hotfix also needs to be on our other long lived branches. We can do this in two ways, we merge/rebase the main in our long lived branches or we cherry pick them. Since cherry picking is a safer approach we will cherry pick:

git checkout developCOMMIT_ID=$(git rev-parse hotfix/branch-1)git cherry-pick $COMMIT_IDgit checkout staginggit cherry-pick $COMMIT_ID

If we continue our normal flow and merge something from develop to staging, then we will notice some inconvenience

git merge develop --no-editgit checkout maingit merge staging --no-editgit log --oneline

This is the output i've got:

7f1f493 (HEAD -> main) Merge branch 'staging' into maine9df087 (staging, develop) Updated readme.mde4430c0 Merge branch 'hotfix/branch-1' into main6e6c71d Added new feature141e865 (hotfix/branch-1) Updated readme.mdab563f6 Initial commit

Remember, you've only created 3 real commits but we have 6 commits in our history. This means this strategy really pollutes our git history. You might think, just use rebase and you'll get a cleaner tree. Which is true, but you will have to resolve trivial rebase conflicts with that approach since it needs to know which commit the code belongs to. You also use git push --force which can have consequences (code loss) if used incorrectly.

Since I have a DevOps background, I see one big major issue. If I go from develop to main, I create a merge commit, so I can't use the binaries created by the develop branch. A hotfix might be present on the main branch but not yet in develop (since someone was sloppy and the maintenance didn't happen yet). It is very prone to errors. Rebasing does not create a merge commit, but it doesn't resolve this issue. You'll have the sha of the latest commit on develop, but you are uncertain that the develop equals main. You could use the binaries that were last created by your develop build in theory, but it's hard to verify if that's the one you want. You can have racing issues, when a develop build didn't finish yet, or a newer one has finished already. You should always try to follow the concept of build once, deploy everywhere. So you don't test binaries on develop, that aren't the binaries going into production. Your dockerfile base image might have gotten a patch, it might create a major issue for you and you will only notice on production.

Review of this approach

We now know how it works, it's quite complex, quite a lot of commands we have to invoke for just getting a feature and a hotfix deployed. Let's analyse the problems here:

- We tested a feature on develop, but we never tested the feature together with the hotfix anywhere before going to production

- We are not able to apply the concept of build once, deploy everywhere. Merging often creates merge commits, which means we can't promote our binaries

- The binaries you are testing on develop are technically not the same as on UAT and production

- The hotfix was not even tested on develop / staging

- High velocity of deployments brings a lot of maintenance with fixing branches

- You have the same commit code, but a different commit sha on staging and develop, which will lead to a strange commit history with duplicates

- Since you have to merge / cherry-pick quite often, chances of a merge conflict are higher

- Quite likely they are also going to be tougher to resolve

So, why is it still popular then? Well, the main benefit is that you can easily know which code is on which environment if you use automated deployments. Beside that, you have a clear seperation between branches that should be stable (main) and unstable (develop). Checking in bad or untested code is not a real threat, it will get spotted before going into prod on your other environments.

My opinion

Personally, for me it's hard to still recommend this approach for most modern software companies. I could only see use cases for companies who have a really low frequency of updates and want that clear seperation between stable and unstable branches. I think however that this approach is too complex in most cases and the disadvantages outweigh the advantages big time. I've also noticed in practice that branch maintenance is often ignored or forgotten which means you are testing on environments without hotfixes and not your final release. In the next section we will discuss Trunk based development, the main principle of trunk based development is that you only have 1 long-lived branch. If you don't, you are not doing TBD in my opinion.

Only one long-lived branch: TBD

Let's simulate our previous hotfix example in trunk based development. If you aren't familiar with trunk based development, don't worry. It's very simple, that's the strength of it. We have one trunk branch (usually called main) and each change or hotfix we want to commit is targetted to the main branch with a feature/hotfix branch PR. There are multiple variations of this one, they all depend on your deployment velocity. We will start with the most simple one.

Hands on

Let's start from a blank canvas again:

cd /rootrm -r mygitrepomkdir mygitrepocd mygitrepogit initgit checkout -b mainecho "Hello world" >> readme.mdgit add .git commit -m "Initial commit"

We will create our hotfix again:

git checkout -b hotfix/branch-1echo "Hello world!" >> readme.mdgit add .git commit -m "Updated readme.md"

And we simulate the feature as well, this time using a feature branch:

git checkout maingit checkout -b feature/branch-1echo "Hi from develop!" >> develop.txtgit add .git commit -m "Added new feature"

Now we can merge, we merge our feature first, then our hotfix like in the previous example:

git checkout maingit merge feature/branch-1 --no-editgit merge hotfix/branch-1 --no-editgit log --oneline

We see the following output:

e323975 (HEAD -> main) Merge branch 'hotfix/branch-1' into main4a7d3ce (feature/branch-1) Added new featureccd225b (hotfix/branch-1) Updated readme.md850c4f5 Initial commit

We only have 4 commits this time, compared to the 6 commits we had earlier. But the main difference is that this is way less complex. There isn't even any maintenance. We can even bring the commit count down to three if we use rebasing instead of merging.

However, we must look at the downsides of this approach. They are the upsides of the previous approach. We lost track of what is deployed on which environment. In most scenario's, we don't want to publish main directly to production but control which specific commit is. We also can't guarantee that main is stable. These problems can be resolved though.

Imagine if we have 3 environments: develop, UAT and production. Develop is our unstable environment, we will just continuously deploy our main branch there. If we want to go to UAT, we make a git tag from the main branch. The git tag triggers a pipeline, if UAT is ok, we approve the next stage of the pipeline and it gets deployed to production. Here, release promotion is easy, the commit sha already exists on main, so we can just move the same binaries from develop to UAT and main.

The unstable branch issue is usually resolved by introducing feature flags. You put your new code behind a feature flag so the code does not get executed on production yet. You should enable the feature flags on development so the features can be tested though. Once features are released you can enable those feature flags on prod (and maybe remove them if stable). This also brings some extra maintenance, which is a downside to TBD.

This branching model could be used for most software companies. They just have to consider if the added risk is worth it and if they can handle the challenges with it. Is there decent code coverage, can we handle the communication regarding feature flags, etc. There are definitely cases where code quality is very important, if lives would depend on it, then gitflow could still be the better approach but that will be the minority of software companies.

TLDR

GitFlow | TBD | |

|---|---|---|

| Git complexity | ❌ Very complex | ✅ Easy |

| Build once, deploy everywhere | ❌ Only for the happy path | ✅ Always possible |

| Hotfixes propagation | ❌ Needs multiple manual interventions | ✅ Just rebase with main |

| Deployment velocity | ❓Possibly high but with plenty of maintenance | ✅ Easily high if you want |

| Develop experience | ❓Strict flows, what is a hotfix/bugfix? | ✅ Always target main, bugfix/hotfix is same |

| Amount of merge conflicts | ❌ A lot of merge conflicts | ✅ Only one merge, just to main |

| Environment visibility | ✅ Easily, if using automated deploys | ❓Relies on CD tooling |

| Stability | ✅ Develop = unstable, main = stable | ❌ Less stable, feature-flags only limit the struggle |

Variations of TBD:

Release flow

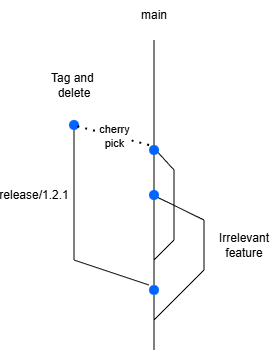

In the previous example I assumed that there were no issues in UAT, which in practice is uncommon, bugs will be there unfortunately. When you want to create a hotfix, the chances are quite likely someone else has committed to the main branch already in the meantime, but you don't want new risks again and you want to stabilize the deployment. We will create release branches for this.

We will start from our commit that we want to release. Instead of fixing the bug directly on the release branch, we fix it on our main. This means all developers will have the fix instantly if they just rebase with main. So the concept stays the same, everything always goes into main, so does our fix. In GitFlow we cherry picked our hotfix from our main to our develop, which could give merge conflicts if develop was a few commits ahead. Now we will cherry pick our fix from the main to our release branch. Our release branch will never be ahead of main, so there can't be any merge conflicts.

After the branch is stabilized, you can release from that branch. You tag the commit and you can delete the branch. You do not merge it back, it's not needed, all the code is in main already. If a hotfix is needed, you can still fallback to the tag. You should also evaluate if a hotfix is really needed, in most cases you can just treat it as a bugfix and deploy with the next release if you have a high velocity with deployments.

You also have some companies that need to maintain multiple versions and apply security patches to those. Kubernetes for example is a product that uses release branches, but they don't delete them since they need those security patches on older releases as well. They apply those security patches on main, and then cherry-pick to the required releases. In theory, those are also long-lived branches (until version is retired), but it doesn't give the same overhead as gitflow and most companies do not need this anyway.

GitHub flow

The concept of GitHub flow is based on very high velocity deployments. Each pull request triggers a deploy, you let it review technically and functionally on the deploy environment. If everyone approves it, it goes into main and it gets deployed to production. The main challenge lies in having an environment for each pr (also called preview environments). The main difference (pun intended) is that the main branch represents what's on production. Your feature branches are the deployments. I'm planning on investigating this more and write another article about this to see how we can combine GitHub flow with preview environments in K8S. So it doesn't use your typical dev / uat / staging / production setup.